By Bernard Freeman

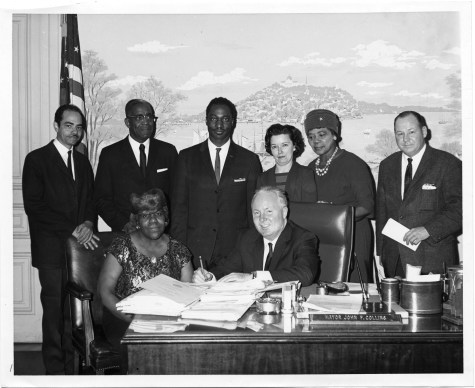

Dr. Charles Richard Drew (top right) is known as the father of blood banking for his work on preserving blood.

Black History Month honors the achievements and recognizes the struggles of African Americans.

Originally founded as Negro History Week by the noted historian Carter G. Woodson and others, the month carries with it an annual theme designated by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.

This year’s theme is Black Health and Wellness, and it’s keyed to exploring more deeply both the diaspora’s access disparities and unique challenges, while also celebrating Black pioneers in medicine.

The COVID-19 pandemic has once again showcased the disparity in health care for Black people and other minorities. In most instances, the problem dates back to prejudices and practices from decades ago, even centuries. But there were great men and women along the way, as well — African Americans who made huge strides for everyone while setting new standards.

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler, for instance, became the first Black woman to earn a medical degree in the U.S. after years of serving as a nurse. Dr. James McCune Smith was the first Black American to earn a medical degree, although he was forced to attend the University of Glasgow due to Jim Crow-era admissions practices in his home country. He later became the first Black person to own and operate his own pharmacy in the U.S.

Dr. Charles Richard Drew is now known as the father of blood banking, after pioneering preservation techniques that made donations far more widespread. Dr. Marilyn Hughes Gaston likewise became a pioneer in the study of sickle cell anemia, leading a groundbreaking 1986 study that paved the way for a national screening program. Dr. Regina Benjamin became America’s 18th surgeon general.

Their achievements stand in direct contrast to the difficulties their community has faced in getting safe, modern, economical health care. Black History Month’s theme of Black Health and Wellness also underscores how the awful traditions of whites-only hospitals, discriminatory insurance policies and neglected Black medical facilities built a foundation of poor medical outcomes and earlier death.

Left to themselves, Black people turned to folk remedies instead of a physician’s care, hearkening back to the diaspora’s African roots. Naturopaths, healers and midwives were commonplace. There was also widespread use of more cost-effective plant-based medicines, including garlic (for high blood pressure) and aloe vera (for issues of the skin). In some cases, those remedies were later validated by scientists — but in the meantime, the differences in how Americans were cared for remained stark.

The 20th and 21st centuries saw huge advancements, including the passage of the Affordable Care Act, but there’s still work to do. This year’s Black History Month theme aims to highlight how the United States continues to fall behind other industrialized nations in providing medical care for all of its citizenry.

History of Observance

The idea of celebrating the undeniable impact of leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Malcolm X and Barack Obama during Black History Month actually started much smaller.

This effort to establish a regular period of remembrance predates them all. Here’s a look back at the history of this special observance.

HOW BLACK HISTORY MONTH STARTED

Historian Carter G. Woodson, a University of Chicago alumnus with a large network of friends and colleagues, joined together with the Rev. Jesse E. Moorland and others to found the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915 — some 15 years before MLK was born. Woodson had come up with the idea after traveling to Washington, D.C., for a three-week event marking the 50th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. He was met there by thousands of others who enjoyed presentations on African Americans’ community’s often-overlooked achievements.

A new tradition was born. Now known as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH), the group has remained focused on Woodson’s original desire to research and inform others about the many advancements made by U.S. citizens of African descent. The first celebration, however, was known as Negro History Week.

The ASALH selected a date in February to mark the occasion, since both Frederick Douglass and Lincoln were born in that month and those dates were already commemorated in the Black community. But they weren’t simply looking back.

Woodson’s stated hope was that understanding history would spur the Black community to greater future achievements. He sent out a news release announcing the first Negro History Week in February 1926.

EXPANSION AND RECOGNITION

Observations of Negro History Week continued to grow in popularity through the ’40s, eventually inspiring other February events like Negro Brotherhood Week. Black history became part of select curricula, too. Woodson passed in the 1950s, as the Civil Rights Movement started to emerge. The idea of lengthening Negro History Week began to take hold, and scattered cities started individually extending their commemorations over the following years.

Woodson often spoke in West Virginia, and Black people there were celebrating Negro History Month as early as 1940s. Cultural activist Fredrick H. Hammaurab did the same in ‘60s-era Chicago. By 1976, President Gerald Ford had officially recognized Black History Month, in an announcement made as part of America’s Bicentennial.

He encouraged U.S. citizens to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history,” and that remains a guiding principle for us all.

Heart Disease Risk

The good news is that African Americans are living longer, as pre-COVID death rates declined about 25% over the previous decade.

Even with those obvious advances, however, Black people are living with and often dying of complications from conditions like high blood pressure that are better managed in other communities.

These outcomes are typically due to economic conditions and access issues that are more common in the African American community. Sometimes, there is a lack of trust because of unfamiliarity, or historical issues with the medical community. Often, they may not see a doctor simply because of cost.

INSIDE THE NUMBERS

Heart disease remains the leading cause of death among African Americans, with increasing numbers among formerly atypical demographics like women and the young. When a chronic illness begins early, it can lead to earlier death.

As it stands, Black people aged 18 to 49 are two times more likely to die from heart disease than whites, according to the CDC. African Americans between 35 and 64 are also 50% more likely to have high blood pressure. Black women are 60% more likely to suffer from hypertension than non-Hispanic white women.

Black History Month’s theme of Black Health and Wellness gives us all a chance to reflect on the simple steps we can take to address heart disease. Your risk is heightened by high blood pressure, obesity and diabetes, issues that also play a role in strokes.

ADDRESSING THE PROBLEM

High blood pressure impacts African Americans more than any other race worldwide, and left untreated, it can do permanent damage long before there are any debilitating symptoms. Hypertension is more severe among Black people, and also tends to develop earlier in their lives.

Start by being aware. Check your blood pressure regularly, even if you don’t have a history of hypertension. Become familiar with your family’s medical history, since that can play a role in developing high blood pressure. If there’s a problem, seek medical attention immediately.

African Americans are also disproportionately suffering from obesity. Nearly 70% of non-Hispanic Black people ages 20 and older, and more than 80% of women, are overweight. A healthy diet can help address this issue, along with a regimen of daily exercise. Similar advice is given to those dealing with diabetes, a major risk factor in both heart disease and stroke. Type 2 diabetes is preventable, and treatable — but you’ll need to develop a plan with your doctor.

Photo credit Harris and Ewing/Wikimedia Commons